Do Calves Need an IBR Vaccine?

Bovilis IBR Marker Live

What is IBR – Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis?

Turning calves out to grass for the first time is rewarding, but ensuring their protection against diseases like IBR (Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis) is crucial for growth and well-being. Rearing healthy calves requires great effort, and vaccinating them against IBR plays a critical role in maintaining herd health.

Minimising the impact of diseases like diarrhea and pneumonia can be challenging. For example, weaning dairy calves, dealing with coccidiosis threats, pneumonia and clostridial vaccination; the calf ‘to do’ list can be comprehensive. So, what about IBR vaccination?

Infection with IBR is widespread in the cattle population in Ireland, with evidence of exposure in over 70% of herds (both beef and dairy). As a result, it is capable of causing disease (both clinical and subclinical) resulting in huge economic losses at farm level through lack of production and treatment costs.

The majority of infections are seen in cattle greater than six months of age, however, all ages are at risk of this virus.

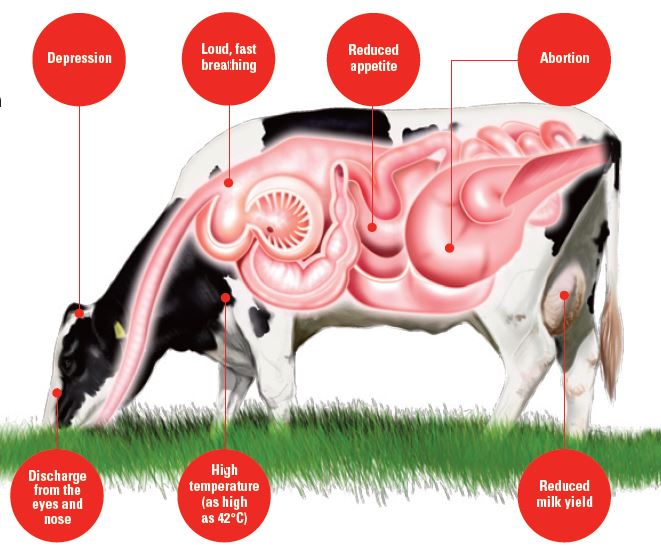

Clinical infections often happen when animals are infected for the first time. These cases may show signs such as discharge from the eyes and nose, loud laboured breathing, and high temperatures. Additionally, affected animals can experience reduced appetite, depression, or even a drop in milk yield and occasional abortion.

Subclinical infections occur without obvious clinical signs and may go unnoticed in a herd. That said, they can still cause losses of up to 2.6 kg of milk per cow per day. Infected animals typically shed high levels of the virus for about two weeks.

At times of stress (e.g. mixing/housing/breeding/calving) the virus can reactivate, and that animal may shed again. Every time an animal sheds the virus it has the potential to infect more herd mates.

How to Control IBR

There are 3 components to controlling this endemic disease:

- Vaccination

- Biosecurity

- Culling

IBR Vaccination – The Key to Protection

- Reduce the number of new infections – Main cause of virus spreading in a herd

- Reduce severity of clinical signs – Limit cost of disease impact

For effective control of IBR, vaccination must:

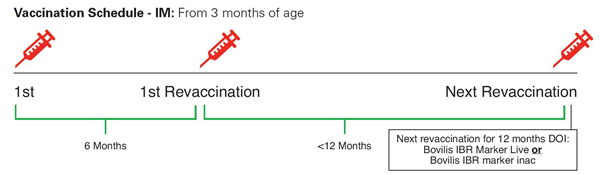

Generally, the time to start vaccination depends on the particular epidemiological situation of each farm. For example, in the absence of virus circulation among the young calf group, vaccination is started at the age of three months, revaccination six months later and all subsequent revaccinations within six to 12 month periods.

This will provide protection against Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis virus and minimise the number of animals that become carriers. In particular, herds that have a moderate to high seroprevalence of IBR, are high-risk and/or have clinical signs are best to remain on a six monthly vaccination programme until the virus is under better control in the herd.

If vaccination needs to be carried out before the age of three months (high prevalence/high-risk herds/disease in calves), then intranasal vaccination is the recommended route in order to overcome maternally derived antibodies.

An intramuscular vaccination programme then commences at three-four months of age, as stated above. Specifically, for the spring calving herd this will mean calves will receive their first dose of a live IBR vaccine in June/July 2021.

Bovilis IBR Marker live

Bovilis IBR marker live provides protection by reducing clinical signs and virus excretion. It is a 2ml dose with a fast onset of immunity (four days after intranasal administration and 14 days after intramuscular administration).

Biosecurity

Biosecurity includes both bio exclusion and bio-containment strategies.

Bio exclusion, which refers to keeping disease out of the herd, is especially important in Ireland due to the frequent movement of cattle. Many herds purchase animals such as stock bulls, use contract rearing for heifers, or attend marts and shows.

Additionally, IBR can travel up to five metres, meaning neighbouring cattle during the grazing season may spread infection — or be infected in return.

Secondly, bio containment (the process of reducing the threat of infection within a herd) relies mainly on herd management strategies such as segregating age groups and, importantly, vaccination.

Culling

Culling of animals which have tested positive for IBR is a quick method to reduce herd prevalence. However, in many herds it is not a practical option as there are simply too many animals which are positive (once infected an animal becomes a life-long carrier) and therefore it would not be economically viable.

In summary, the majority of herds in Ireland are of medium or high seroprevalence, so vaccination with a live IBR marker vaccine combined with biosecurity are the most practical and appropriate control methods.

Still, many herds are missing a trick by only vaccinating the cows. This approach controls clinical signs and the impact of IBR on production but does not necessarily reduce the spread to unvaccinated younger cattle or the number of new infections each year.

As a result, whole herd vaccination aims to reduce IBR levels gradually across the herd. So, in answer to the original question — yes, calves should be vaccinated against IBR.

TAGS

Product Focus

Related Video

To activate the video player please allow cookies in category ‘Performance and Operation’ and refresh this page.

Related Articles

Sign up to Bovilis® product and event information

MSD Animal Health

Red Oak North, South County Business Park, Leopardstown,

Dublin 18, Ireland

vet-support.ie@msd.com

PHONE

CATTLE DISEASES